Flair Magazine by Fleur Cowles as never seen before. 1950

1950. The Turning Point in Magazine Publishing.

In 1950, two new magazines were published. Both were highly innovative and destined to strongly influence all publishing in the following years.

The first was Portfolio, by Alexei Brodovitch, the Art Director of Harper’s Bazaar, which had revolutionized magazine design in previous years. The second one was Flair by Fleur Cowles.

Both were produced without budget limits, and both ceased publication after one year only because of the cost of production, which killed the magazines since the expensive special costs could not be supported in the long run.

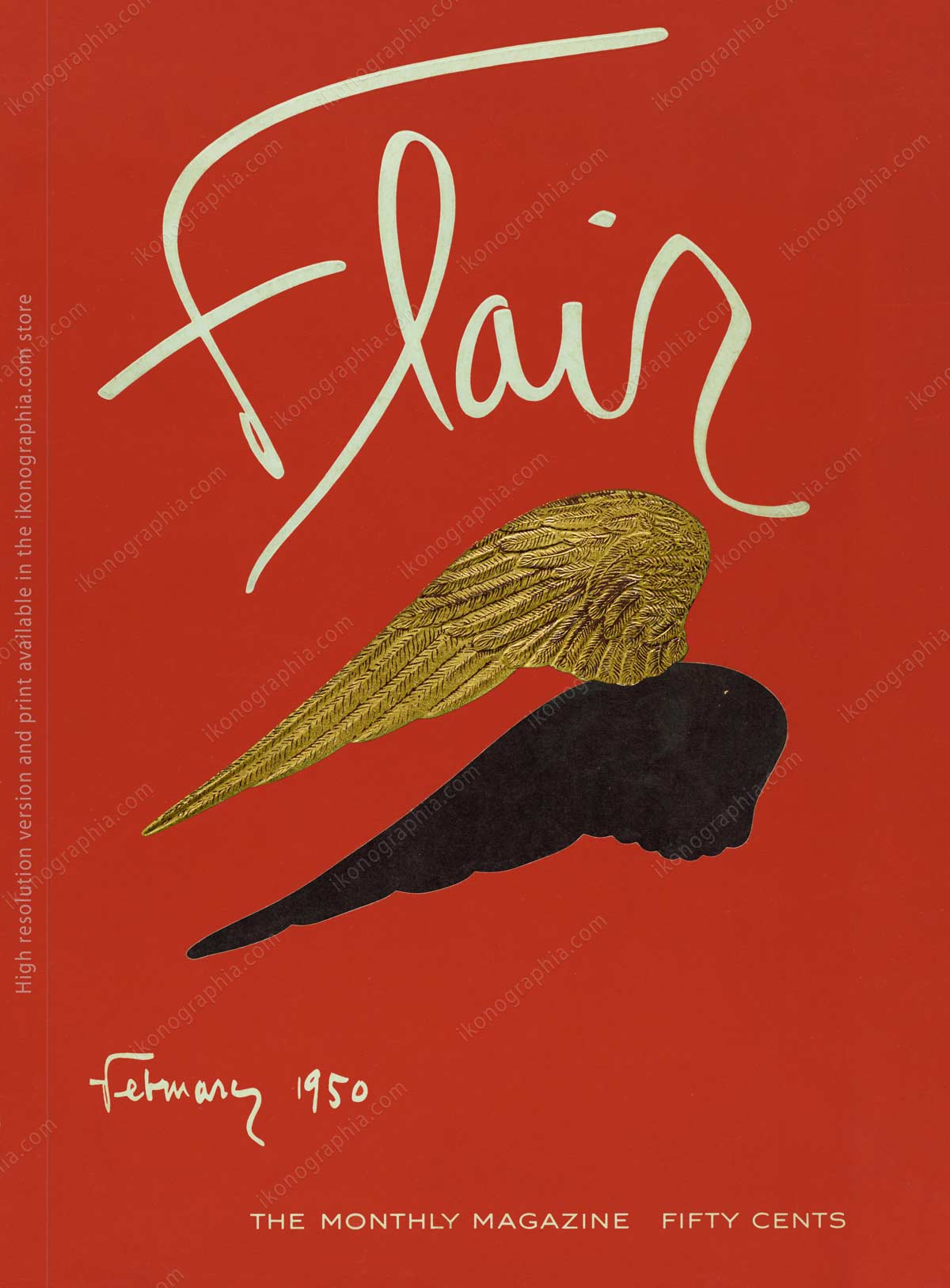

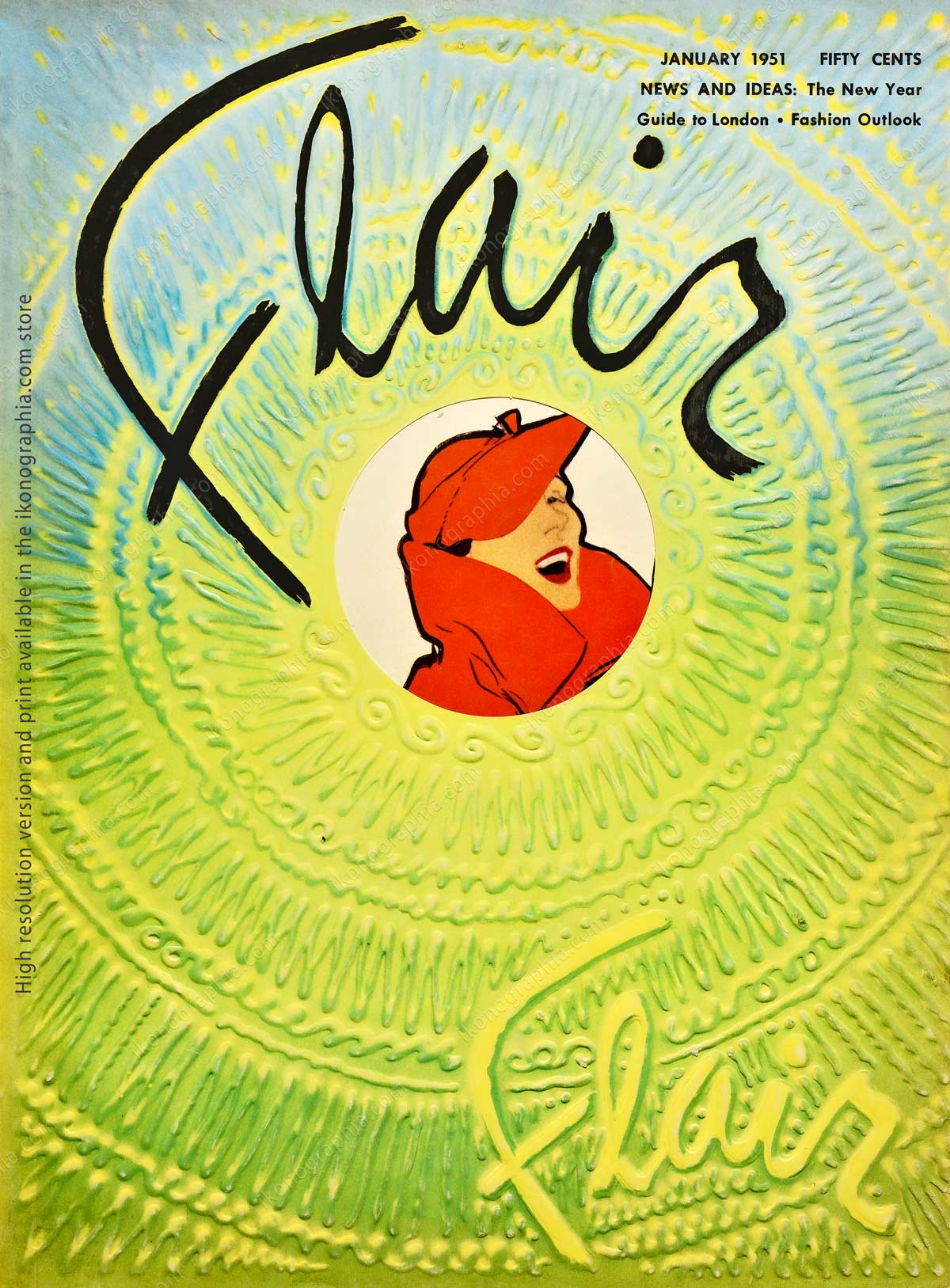

The first issue of Flair Magazine, February 1950, and the first issue of Portfolio, Winter 1950.

Flair. “The Monthly Magazine for Moderns”

On September 1949, Fleur Cowles released s a pre-publication advertiser’s issue announcing Flair as ‘the monthly magazine for moderns.’ Here is an excerpt from the Time Magazine review.

Fleur’s Flair, which will be shown this week in a limited edition to 5,000 potential advertisers and subscribers, looks like a fancy bouillabaisse of Vogue, Town & Country, Holiday, etc. By covering “fashion, art, literature, travel, decor, theater and entertainment,” Editor Cowles expects to lure enough readers to guarantee advertisers a circulation of 200,000 (at 50¢ a copy) at the start.

Flair’s sample issue has an off-white hardcover with a second illustrated cover visible through a triangular peephole. Flair abounds with other tricks. There is an accordion-style pull-out on interior decoration, a pocket-sized book insert, a swatch of cotton fabric, and even a page written in invisible ink that can be read when heated by a lighted match.

Source >

Flair, according to Fleur Cowles

Cowles wanted something that was, above all things, tactile and surprising, like a children’s book for adults. Below is her presentation in the first number of February 1950, printed in gold on a special blue luxury paper.

There have been Great adventures in paper and in printing and in the presentation of the graphic arts in the last decade… Unhappily, few of them for the public at large.

I have longed to introduce a magazine daring enough to utilize the best of these adventures. A magazine which combines for the first time under one set of covers, the best in the arts: literature, fashion, humour, decoration, travel and entertainment.

This copy of Flair shows that it can be done; it is proof that a magazine need no longer be stolidly frozen to the familiar format. Flair can an will, vary from issue to issue, from year to year, assuring you that most delicious of rewards – a sense of surprise, a joy of discovery. For the young in heart, men and women, I believe our efforts will help give a vital contemporary direction and fullness to American life.

Fleur Cowles, Editor

Flair N.1, February 1950. The presentation of Flair hand-written by the Editor, Fleur Cowles.

An innovative Magazine.

Fleur Cowles was a design catalyst, creating an innovative magazine not just for 1950.

The magazine pages had hinged doors, pamphlet inserts, and spreads with flipbooks with captions underneath the main image. The pages did not come in a single stock, with a mix of papers in the same issue, from heavy cardstock to slight, onionskin translucent prints to glossy, smooth, and slippery pages.

Flair was designed to be a sensory feast for the readers that could touch, smell and enjoy the always-different art.

Someone defined Flair’s design as an “elegant cacophony”; others “a fancy bouillabaisse of Vogue, Town & Country, Holiday.”

Call it as you prefer; Flair was and still is unique.

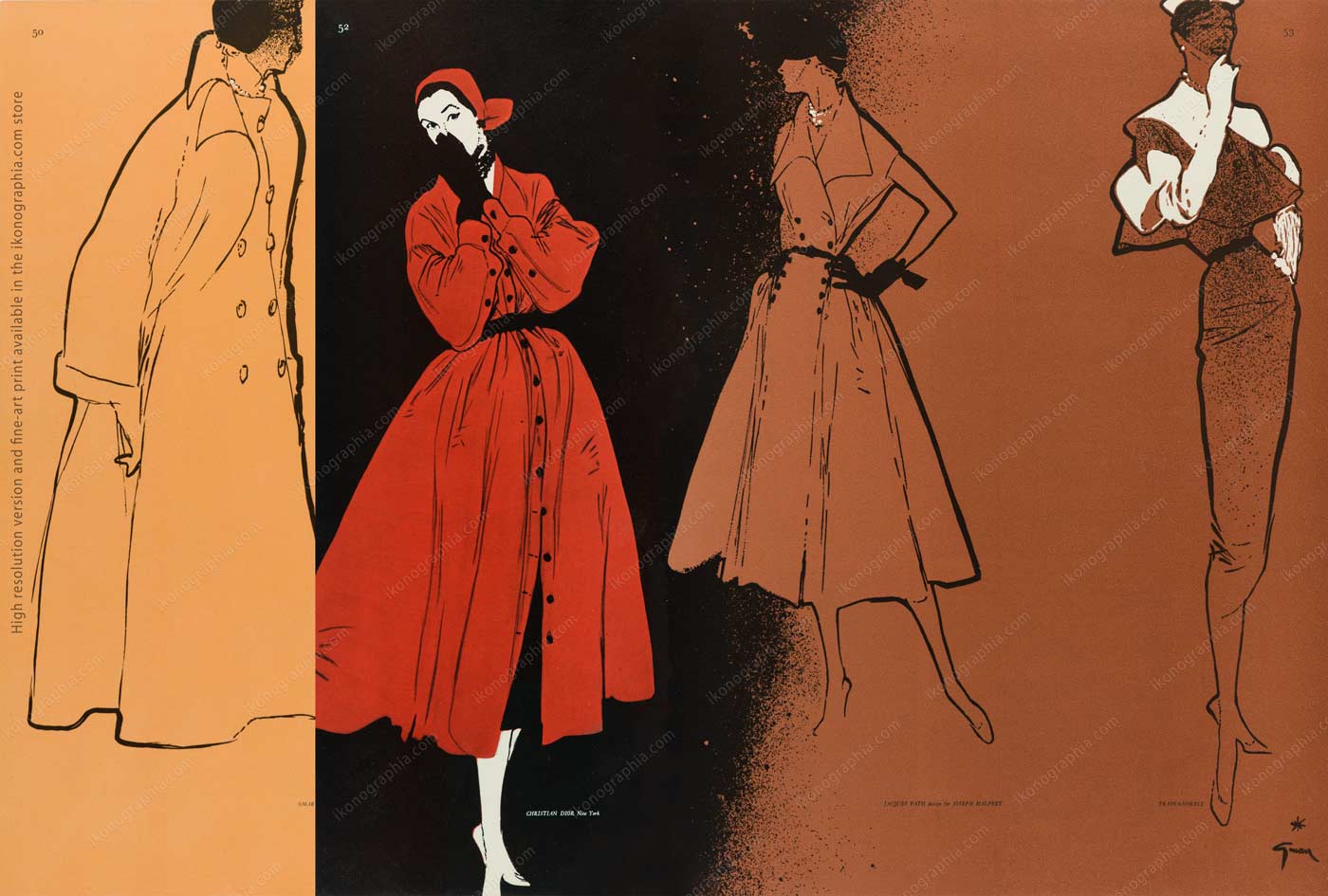

You are known by the color you keep. Flair Magazine, February 1950. Pages 50/53. Artwork by Renè Gruau.

Creations by Omar Kiam, Christian Dior of New York, Jaques Fath for Joseph Halpert, and Traina Norell.

Use arrows to flip pages.

FULL PAGES TEXT

YOU ARE KNOWN BY THE COLORS YOU KEEP.

Color may be the expression by which your world knows you best. You must unerringly know your range; perhaps the whole gamut is yours, perhaps only one color or two. The colors you wear should not be random choices: they are convictions to be carried through with unfaltering assurance.

Consider a great-coat (left), its collar jutting out like a separate jacket, in a peach beige with an affinity for navy blue. Against a wool skirt and velvet collar of black, a tawny beige cavalry twill jacket, a flash of red in the print blouse (right). Turn the flap and find spring’s surprise, blazing red: a swaggering silk taffeta coat over a black strapless dress. In the beige range again, iridescent shantung takes on a true taupe cast, the sharpness of black accents. And the perennial freshness of small black and white checks is given further élan by the wand cut of a dress, a pullover jacket’s starchy, winged white linen collars and cuffs.

Credits: left: OMAR KIAN of BEN REIG. center and right: TRAINA-NORELL.

Autumn is a city season. Flair Magazine, September 1950, pages 36-37. Use arrows to flip pages.

Below is the original magazine with pages 36 to 39 with flaps.

FULL PAGES TEXT

All Brim or All Crown. Photos by Maria Martel, Flair , March 1950 Pages 46, 49, including the flap page. Pages transcript: All Brim or All Crown. There are two hats this spring—the restless free shape flaring into space like a Calder mobile; or the close, crushed-to-the-head cap. The free shapes: Lilly Daché’s milan wheat (page 46), its deep cantilever brim faced in black velvet. Braagaard’s white organdy (above) with bands of stitching, bound in navy blue to accent its adventurous outlines. The close caps: 1. A coif, half purple and half white violets. 2. A cushion beret with a mound of pink roses shrouded in moss green veiling—the whole netted in heavy black mesh. 3. A small hillock of lilacs, green leaves and pink roses, springing from a white organdy cap. (These three, Lilly Daché.) 4. A cap and a crushed side bow of amber satin. 5. A lightly brimmed cap of lemon yellow felt, narrowly belted in rhinestones; a honey-colored face-veil. (These two, Mme. Andrée at Bonwit Teller.) 6. A minute helmet of pale blue straw with a bird on the brim and a misty black nose-veil. (Made to order at Bergdorf Goodman.)

Captions page 46: DIAMOND EARRINGS, CARTIER.

Caption, page 47: 2. RUBY AND DIAMONDS EARRINGS, VAN CLEEF & ARPELS.

Caption, page 48: PWARL AND DIAMON EARRINGS, SEAMAN SCHEPPS.

Caption, page 49: PEARL NECKLACES, DAVID WEBB.

Fashion is an Eye. Flair Magazine, February 1950. Photo by George Hoyningen-Huene.

Use arrows to flip the page

FULL PAGES TEXT

Fashion is an Eye.

You will find her, the brooding and uncertain woman opposite, wherever a dress may be bought.

The scene might be the Place Vendome, a New York store, a small-town dress shop. Maybe she hasn’t even bothered to ask the price; or she might have scrimped for months to allow herself this one purchase. Whoever she may be, whatever her purse, she is a soul in misery — a fact the men in her life would never suspect. Probably she could not tell them why.

The unwelcome presence of other customers may have contributed. The most casual glance she interprets as a hard scrutiny, and her pleasant suit suddenly appears faded, worn.

The sales-girl may have held up one dress too insistently and aroused the cringing suspicion that some impossible thing is being palmed off on an easy victim. Or, worse mischance of all, this unhappy woman may have faced the mirror and found in its sly depths an unfamiliar reflection, so that every secret doubt she has ever had as to her looks and desirability now furiously possesses her.

At last she has decided; she is free to lift herself from her chair. How could she be so uncertain, so confused? Yet often she has reached the street before she regains her normal self-possession and sees, sees with her own eyes, again. What causes this temporary blindness? Not too little; perhaps too much. Ironically, as far as American women are concerned, this symptom of insecurity may be all the greater because fashion has never given them a wider choice nor made the work of the finest designers available to so many.

The public is familiar as never before with significant trends and important names in fashion — a result highly praiseworthy in all respects but one.

Fashion has ceased to be personal. In choosing a dress, the American woman is aware of many eyes upon her, and in turn she tries to judge what is before her by every high standard she knows . . . except her own. Fashion is an eye.

Every woman’s eye. Your eye. And inevitably, fashion begins with the inner eye, with self-awareness, with understanding of all your powers, physical, mental, spiritual. It must calmly estimate all that you may claim as potentials for beauty. It demands the fullest expression of your own nature. It insists that you absorb the influences, the knowledges, the disciplines that will be permanently useful to you. It gives mature direction to the outer eye, guiding it to those possessions that are rightfully yours.

It forbids you from seeking refuge in those eccentricities of taste that reveal an insecurity far more destructive than the most slavish acceptance of the usual arbitrary norms.

It allows you to contemplate the fashions that FLAIR will report for you, to claim only those that are your own. Serene and sure, your eye will no longer waver from the image of beauty you have set for yourself. You will then be free to communicate your gaiety, your warmth, your self-confidence.

HOYNINGEN-HUENE. DIAMONDS BY HARRY WINSTON

All Brim or All Crown. Photos by Maria Martel, Flair, March 1950, pages 46-47. Use arrows to flip pages.

FULL PAGES TEXT

All Brim or All Crown. Photos by Maria Martel, Flair , March 1950 Pages 46, 49, including the flap page. Pages transcript: All Brim or All Crown. There are two hats this spring—the restless free shape flaring into space like a Calder mobile; or the close, crushed-to-the-head cap. The free shapes: Lilly Daché’s milan wheat (page 46), its deep cantilever brim faced in black velvet. Braagaard’s white organdy (above) with bands of stitching, bound in navy blue to accent its adventurous outlines. The close caps: 1. A coif, half purple and half white violets. 2. A cushion beret with a mound of pink roses shrouded in moss green veiling—the whole netted in heavy black mesh. 3. A small hillock of lilacs, green leaves and pink roses, springing from a white organdy cap. (These three, Lilly Daché.) 4. A cap and a crushed side bow of amber satin. 5. A lightly brimmed cap of lemon yellow felt, narrowly belted in rhinestones; a honey-colored face-veil. (These two, Mme. Andrée at Bonwit Teller.) 6. A minute helmet of pale blue straw with a bird on the brim and a misty black nose-veil. (Made to order at Bergdorf Goodman.)

Captions page 46: DIAMOND EARRINGS, CARTIER.

Caption, page 47: 2. RUBY AND DIAMONDS EARRINGS, VAN CLEEF & ARPELS.

Caption, page 48: PWARL AND DIAMON EARRINGS, SEAMAN SCHEPPS.

Caption, page 49: PEARL NECKLACES, DAVID WEBB.

Flair, May 1950. A double page from the Spring number. The issue, dedicated to the rose, was infused with an expensive rose fragrance, decades before scent strips became common in magazines.

FULL PAGES TEXT

The Opening of the Social Season.

How the Members of the Beau Monde Will Spend What Is Left of Their War-Time Income.

THE RESTAURANTS.

The season in the restaurants has opened strong. And the worst of it is that the ladies will spend all their time in these blessed robbers’ dens. Tell a woman that her place is in the home and — but you wouldn’t do anything as rude as that, would you? There are two other discouraging things about women in a restaurant: first, that they won’t ever go home, and second, that they won’t ever sit down. Here we see a tragedy illustrating both of these points. Muriel, who long ago finished her luncheon simply will not join the gentleman in the hallway (the one who looks a little like President Wilson), although the poor creature has been waiting for twenty minutes. And her charming little vis a vis, Esme by name (the one with the lap dog that looks like a three-leaved clover), has, on her side, been keeping her fiance standing at attention for a similar period of time — and, all because the two dears have such thrilling and wonderful things to talk about.

THE HORSE SHOW.

Here we see the horse show in full blast. Here you will see everybody happy, everybody occupied, scandals energetically and effectually discussed, meetings arranged in whispers, society reporters calling everybody by their wrong names, and everybody paying the strictest attention to everything about them — except the horses.

THE ART SHOWS.

Below we see the opening of the Vorticist Sculpture Salon, a debauch in marble that always brings out a full quota of the artistic cognoscenti of the town. Bohemia always appears in goodly numbers at these charming little revels in stone. The extraordinary thing about much of the new sculpture is that it looks like illustrations for those wonderful books on hygiene, in which ladies’ are taking their matutinal exercises—by correspondence, of course. Take, for instance, the case of the delicate little gem entitled “Love” in this illustration. Captain De Pluyster who is viewing it in company with his fiancée, Miss Corinna Walpole, is listening to her: “Oh, that’s an easy one. I do that twenty times, every morning, just before my bath.”

THE FASHION FÊTES:

Perhaps the most delightful social occasion of all — at least as far as married men are concerned — is the winter Fashion Fete at Luciline’s select little dressmaking establishment. In the picture, you will observe a married gentleman, accompanied by his gross tonnage. The poor man is not at all listening to Mme. Luciline; no, he is gazing wistfully and, with eyes aflame, toward the wholly divine young ladies who, every season, do so much toward making the happy modes and unmaking the unhappy marriages. “How different would have been my life,” he reflects, “had I met one of those limp and sinuous sirens before I took up with my Henrietta.”

A visionary talent-hiring editor

Conceived and produced by visionary editor Fleur Cowles, Flair magazine existed for only one year and twelve issues, from February 1950 to January 1951. The magazine combined art, fashion, travel, and reportage to take the most out of its Editor’s formidable ability to promote European and American talent.

Cowles hired the best illustrators and photographers. The most impacting was Gruau at the peak of his career.

In one year only, Flair published the work of Jean Cocteau, Lucien Freud, Saul Steinberg, Salvador Dalí, Simone De Beauvoir, Walker Evans, Bernard Baruch, George Bernard Shaw, Tennessee Williams, Gloria Swanson, Eleanor Roosevelt, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Colette.

Flair, March 1950. Paris Collections Spring 1950. This is the shade of tangerine that is everywhere in Paris, and will be everywhere in America. From left, creations by Dior, Dior, and Molyneux. Art by René Gruau., left page.

FULL PAGES TEXT

Paris Collections Spring 1950. This is the shade of tangerine that is everywhere in Paris, and will be everywhere in America.

Pages text transcript

FIRST . . . THIS IS THE SHADE OF TANGERINE THAT IS EVERYWHERE IN PARIS, WILL BE EVERYWHERE IN AMERICA IN NEWS: The straight and narrow silhouette sometimes relieved by a bloused back, a big bib-collar, a bow of fantastic size; or by over-all tucking, ruching, fluttering petals; a floor-length pouf or panel; a starched or pleated flare below the hips, below the knees, toward the hem.

. . .The occasional break from the straight into belling and even bouffant evening skirts…. The fluctuating hemline-in-transition—an average fifteen inches for day; every length for evening.

… IN COLOR White, white everywhere; then black and white, navy and white, and a ranging spectrum of blond and amber tones culminating in striking doses everywhere of tangerine.

. . . IN SPOT NEWS: The décolleté, cuffed, horseshoe neckline on suits and street dresses. . . . Dior’s mannish dusters of silk tussor in natural or in pale colors over darker dresses; his fabulously tailored chiffon evening coats. . . . The flowing peignoir coat, often sleeveless. . . . The narrow sleeveless dress. . . . The overlong, crushed-down gloves worn with both.

… IN PROPHETIC TENDENCY: The straightening silhouette, the heightening hemline, the slowly but surely descending waistline. Opposite: Dior’s black taffeta with an immense white bib-collar, starched and nun-like, tied with a whisker bow of black net. Right: Dior’s black-and-white tweed smoking jacket, narrowed at the hem, its deep horseshoe neckline cuffed with tuxedo revers; over a black wool dress with a white Byronic collar, a big black taffeta bow tied outside. Far right: Molyneux’s double-breasted gray wool with a bril-handy cut envelope fold at the front of its skirt, a taffeta sash tied in a bold bow. An optional straight, pleated wool overskirt changes its looks but not its lines.

About Fleur Cowles. A short bio.

Portrait of Fleur Cowles, by René Gruau.

Courtesy: Christie's:

Fleur Fenton Cowles (1908 – 2009) was an American writer, publisher and editor best known as the creative force behind the short-lived Flair Magazine.

She was a writer, advertising agency executive, and publisher of Look Magazine when she convinced his third husband, Gardner Cowles, Jr., to finance Flair's Launch.

"I've worked hard, made a fortune, and did it in a man's world, but always, ruthlessly, and cruelly insistently, I have tried to keep feminine."

"Most women married to rich men hope for a yacht or racehorses or more jewels. But I secretly longed for the opportunity to create a 'magazine-jewel' which would reflect the real me". (From her 1996 memories.)

In 1955 she moved to London Piccadilly Circus, where she lived lavishly until she died in 2009. She was friends with diplomats, movie stars, and the Queen Mother.